How food workers are building solidarity across borders and industries

How food workers are building solidarity across borders and industries

Image: Action outside a New York Starbucks, in solidarity with migrant workers who went on strike over COVID-19 safety at Martin’s Family Fruit Farm in Ontario. Nov 25, 2020. Photo: Justicia for Migrant Workers

What does a Starbucks in Mexico have to do with an apple farm in Ontario? A lot, it turns out.

Last fall, a group of migrant agricultural workers in Vienna, Ontario, staged a wildcat strike at Martin’s Family Fruit Farm, which supplies apples used to make apple chips sold at Starbucks. In an act of support and solidarity, the international Food Chain Workers Alliance coordinated actions at over 20 Starbucks locations in Canada, the US, and Mexico.

This cross-industry, cross-border organizing exemplifies the work of the Food Chain Workers Alliance (FCWA), which aims to cultivate solidarity and build power for workers across the entire food chain.

The FCWA is a coalition of unions and worker advocacy groups in different food industries — from planting and harvesting, to processing, to selling and serving — with members in both the US and Canada.

The strike at Martin’s and actions at Starbucks were initially sparked by a COVID-19 outbreak at Martin’s Family Fruit Farm at the end of October 2020, and management’s response.

Following the outbreak, migrant farmworkers refused to work until they could all confirm whether or not they had contracted the COVID-19 virus. However, the employer refused.

“A group of workers [at Martin’s] withheld their labor for, I believe, a day and a half,” explains Chris Ramsaroop, and organizer with Justicia 4 Migrant Workers (J4MW), a group supporting migrant workers in Ontario and British Columbia. “They then were threatened, you know, if they didn't go back to work, they would be sent home.”

For migrant farmworkers in Canada through the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program, their status is directly tied to their employment. If they are fired, they are deported. And if they are deported, there is no guarantee they will be called back for the following season.

The Media Co-op spoke to a former worker who participated in the strike. They preferred to remain anonymous to protect against reprisals.

They described a fellow worker exhibiting symptoms a few months into the 2020 agricultural working season, and the employer requiring COVID tests for the rest of the workers.

When workers were told they would not receive results for a few days but would have to continue working in the meantime, they then decided to go on a strike. “We were planning to wait a couple of days and go out and work,” the worker tells the Media Co-op, “But they said no, we have to go out. We were scared to go out and work.”

“We want to do the test and get the result, meaning we can go and work and we don’t have to be scared of each other, or to be around each other,” they said.

The worker also shared that this 2021 season, some workers who participated in the 2020 strike were only called to work around June or July, versus the usual start to the season in April. A shorter work season means less income.

“It’s serious on us around here, and we have no representative,” the worker said about the experience of migrant workers in the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program. Agricultural workers, whose work is governed by the provincial Agricultural Employees Protection Act rather than the Ontario Labour Relations Act, cannot join a union.

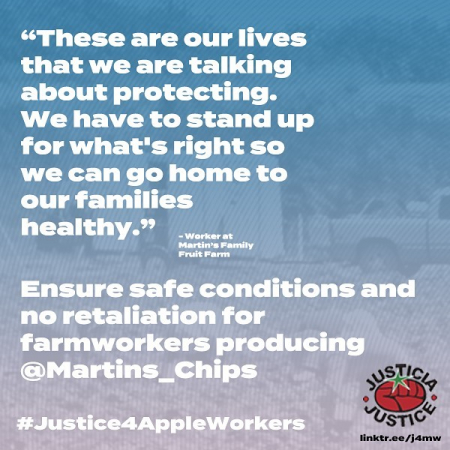

Image: Justicia for Migrant Workers poster published in advance of the solidarity actions at Starbucks locations in November 2020.

When the COVID-19 test results came, the worker tells the Media Co-op, about 15 to 20 workers in one house tested positive, and were sent to a hotel for isolation.

Despite the risk and the consequences, they stand by the choice to strike.

“It was really good that we were striking, that we didn’t want to go and work, before getting results,” they say. They add that if they had gone out to work, it could have made the outbreak at Martin’s even worse.

A show of solidarity

A Canadian member of the Food Chain Workers Alliance (FCWA), J4MW planned a day of action on November 25th, 2020, a month after the outbreak, to demand employer Martin’s Family Fruit Farm make a commitment to having no reprisals against agricultural workers.

J4MW is a grassroots volunteer-run organizing collective that supports and advocates for migrant farmworkers participating in the Seasonal Agricultural Workers Program and the Low Skilled Workers Program (two streams of Canada’s Temporary Foreign Worker Program), as well as farmworkers without status.

The FCWA participated in the delegation visits at Starbucks locations across North America on the same day.

Ramsaroop says the Alliance’s work and this action are “what resistance looks like.”

“So first of all, that the workers undertook this form of resistance is imperative and critical,” he says. “But the second thing to that, through the Food Chain Workers Alliance, we've had different member organizations in multiple cities undertake a rapid response in support of these workers. And we had people as far as Mexico, go into their Starbucks, trying to, you know, to send a message about racial justice. It shows the strength of what solidarity looks like, across the continent.”

Image: An individual in Mexico City takes part in the action at a local Starbucks, in solidarity with migrant workers who went on strike at Martin’s Family Fruit Farm in Ontario. Nov 25, 2020. Photo: Justicia for Migrant Workers

Elizabeth Walle is a Development Coordinator with the Alliance, and coordinated US delegation visits. She says the reaction of Starbucks workers at US locations was “pretty typical,” and they accepted a letter from delegates about the action — when managers were available the letter was presented to them — and they said “they would share it with the higher ups,” she told the Media Co-op via email.

Ramsaroop was part of the delegation to an Ontario Starbucks and described positive conversations with Starbucks employees about the action, and that they seemed to connect with the message of a shared workers’ struggle.

“In the pandemic, frontline workers at a coffee shop, or a farm worker, or across the food chain, have been declared as essential workers.” Ramsaroop says. “They've been screwed over while the corporations that they work for are having these exorbitant profits. We see forms of commonality, you know, across the food chain.”

The realities of migrant agricultural work

Through the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program, workers arrive every spring in Canada from their home countries and work for the season, then return to their home countries after the harvest. The majority are from Latin America and the Caribbean, with some workers from Asia. They are usually then called back the next year.

However, workers are never guaranteed that they will be called back for the next year, and they don’t find out if they are called back until they are in their home country.

Whether migrant farmworkers push back against workplace issues or not, there is always a risk that they will not be called back the following season. This puts workers in an extremely precarious position while in Canada, and prevents them from being able to advocate for basic workplace rights, including health and safety measures.

“One of the things I think that the employers or the government officials always seem to rely on is that any worker — particularly racialized workers in a rural or isolated community — they rely on this [isolation] to try to create this kind of sense of silence,” says Ramsaroop. “And [they] hope that nobody's going to pick up or try to encourage campaigns of solidarity.”

Ramsaroop explains that a worker at Martin’s filed for an Occupational Health and Safety change that did lead to some changes at that workplace.

“We know that farmworkers in Ontario paid a heavy toll,” says Alliance Co-Director Sonia Singh, of the impact of COVID-19 on migrant agricultural workers. “There was the level of outbreaks and the waves. That migrant workers were affected was predictable and heartbreaking at the same time.”

According to Labour Minister Monte McNaughton, 12% of migrant farmworkers in Ontario tested positive for COVID-19 in 2020, though actual totals could be higher. Farms across the provinces saw outbreaks throughout the pandemic involving hundreds of workers at a time. At least four workers have died as a result of contracting the virus.

As of October 28, 2021, Public Health Ontario reported 4,067 total cases per 100,000 Ontarians throughout the entire pandemic, or approximately 4%.

Ramsaroop says the solidarity from FCWA was noticed and appreciated by Martin’s workers. “This is definitely a morale booster. It definitely is. And it shows once again, that workers, community members are organizing across the supply chain, and across different jurisdictions,” he says. “When we share this information with other workers, it's a morale boost across the entire sector. Across Canada, when one worker fights, other workers see this as a fight for their struggle.”

The impact of actions like this one stretches beyond the connection between Ontario apples and prepackaged snacks sold at Starbucks. What’s important is the building of solidarity across countries, across continents. It’s about building power for a huge number of working people. As the struggle for workers in the food chain persists, these connections, this kind of solidarity, must continue also.