Coroner’s Inquest into RCMP Killing of Community Organizer Barry Shantz Begins

Coroner’s Inquest into RCMP Killing of Community Organizer Barry Shantz Begins

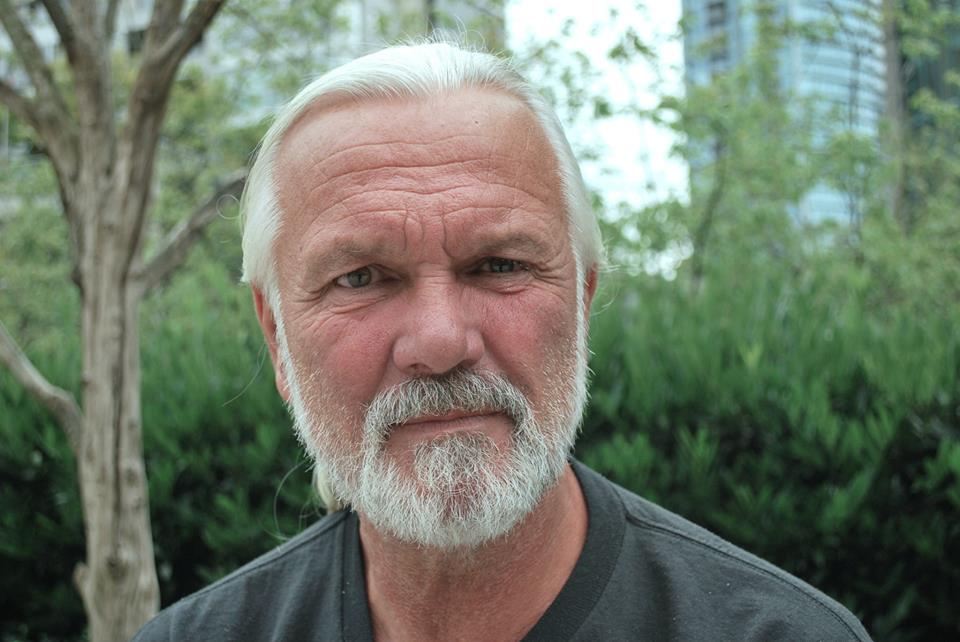

RCMP shot and killed community organizer Barry Shantz (63) in Lytton, British Columbia, in the afternoon of January 13, 2020, while he was in distress. On July 4, 2023, the coroner’s inquest into the police killing begins at coroner’s court in Burnaby.

RCMP killed Barry Shantz at a home in the 1000 block of McIntyre Road shortly after 2 PM. According to the Independent Investigations Office (IIO), the agency that examines cases of police harm to civilians in the province, RCMP went to the home at around 8 AM in response to reports of a man in some type of distress. The IIO report that an emergency response team and a crisis negotiator were also called in.

An RCMP press release claimed that “an interaction between the man and police” ended with shots being fired by the RCMP. It has since been reported that Mr. Shantz exited the home with a weapon, and police officers opened fire. He was pronounced dead at the scene. Family members have since suggested that Mr. Shantz was intending to surrender.

The IIO cleared the officers who killed Barry Shantz in October 2020. They determined the officers to be at risk of “grievous bodily harm or death” during a six-hour standoff. This decision was made on the basis of Mr. Shantz having a firearm, though the report noted that at no time did he point the weapon at officers.

A Globally Recognized Activist

Barry Shantz was a well-known and respected community organizer acting in support of unhoused people and drug users. He was one of the founders of the BC-Yukon Association of Drug War Survivors, and he worked for years advocating for unhoused people in the Fraser Valley, most notably for rights of unhoused people to live in encampments.

His dauntless efforts fighting the City of Abbotsford for the rights of people to camp overnight in a city park were recognized globally. In 2015 he was at the centre of a landmark court victory that won a legal precedent throughout BC for unhoused people maintaining encampments.

Longtime community organizer Ann Livingston, who worked with Barry Shantz in the BC-Yukon Association of Drug War Survivors, recalled shortly after the killing, “He was so respected and loved in Abbotsford. He stuck with those guys, showed up with coffee and donuts, loved everyone — he was a real profound force. I think Barry will be remembered as a hero, as someone who was uncompromising and vigilant. He just kept it up. Other people would drop the ball and he just kept it going. He was a real hard worker and he kept real solidarity with the guys on the street.”

Ward Draper, who also worked with Barry Shantz around issues of homelessness and housing in Abbotsford, believed that those struggles, and the harassment by state actors it entails, took their toll over time. Following the killing he said, “It took its toll on him in many ways, physically, psychologically, economically. It did cost him a lot. And now he got killed by the police.” Draper noted that Mr. Shantz was nearly blind in addition to dealing with serious mental health issues.

He agreed that Barry Shantz leaves an important legacy: “Barry contributed significantly to reforms in Canada and how we address drug use policy, contributed significantly to how we address some homeless issues — particularly with camping in the park and being able to do that now overnight in BC. He’s done some things that weren’t the greatest but he did some things that were really significant, and were beneficial to tens of thousands of Canadians.”

Cops Are Not Care

Marilyn Farquhar, Barry Shantz’s younger sister, has said that he struggled with mental health issues and post-traumatic stress disorder from time spent in a US prison. She said at the time, “He was at my house in September and he shared with me his concerns. I knew he was struggling. I didn’t realize to what extent. When he was at my house, he said he wanted his miracle.”

She has been an advocate for her brother since his killing by police and has said that the killing clearly shows shortcomings in the way police engage in encounters between officers and people experiencing mental health crises. “We want to challenge them … There's a lot I’d like to see changed. I’d like to see people come to the table ... and figure out how we can move forward.”

Farquhar points out the extreme violence deployed against her brother, and the massive resources at the disposal of police, all without a single mental health care provider being brought to the scene. Indeed, the tools of violence deployed against Barry Shantz are staggering. “Thirty armed officers, two snipers, a helicopter and canine unit … (They) used that helicopter to bring in officers. Why couldn’t you use that helicopter to bring in a mental-health professional? … They had six hours.”

Her hope has been for care-based responses to mental health calls. In her words, “The first thing is, do we have to result to fatally killing somebody and are there other options that weren't exhausted when you jumped to that one? I can see places that were skipped and missed.”

In the strongest terms she asks, “Can we not agree that killing someone isn't what we should be doing?”

Not Independent Oversight

Farquhar previously filed a complaint with the Civilian Review Complaints Commission (CRCC) over her brother’s killing. She has been openly and steadfastly critical of the IIO and the stalling of investigations into her brother’s killing. She has pointed out the lack of independence in the IIO, an agency that has former cops as investigators and relies on police for training. As she told Abbotsford News, “My experience with the Independent Investigations Office (IIO) has not been a good one. Right in their name, (it says) independent. I have always felt, in my experience, there was no independence. It was heavily biased.” This is an experience shared by many family members of people killed by police in BC.

Incredibly, in response to her question about why mental health professionals were not sent out, Ron MacDonald, the IIO chief civilian director said in a news conference after the IIO report was released, “Unfortunately, in the time available, that didn’t pan out.”

This is not an answer. It is a condemnation of the state’s prioritizing of police over all other social funding and the callousness of the oversight body as well.

The Inquest and Its Limits

The coroner’s inquest cannot assign legal blame. It is only tasked with establishing the facts around the cause of death and make recommendations to prevent deaths under similar circumstances in future. This means that it will not pursue structural issues like the role of policing as an institution of class violence. It is unlikely that recommendations such as defunding and dismantling police and building up peer-led, non-police, community resources and responses to health care crises will be on the table. Like clockwork, such inquests almost exclusively recommend such failed non-measures as more police training (which is even more resources to police forces) and body cameras (again more resources for police, ones that simply expand surveillance)

The livestream for the inquest and list of witnesses can be found at the BC Coroners Service website.