A Decade of Resistance and Renewal

A Decade of Resistance and Renewal

On December 3rd of 2002, members of Grassy Narrows First Nation launched a direct action blockade to prevent the passage of logging trucks and equipment through their traditional territory. This December marks the 10th anniversary of the Grassy Narrows blockade, now the longest running logging blockade in Canadian history. Located fifty miles north of Kenora (a small Canadian city on the north shore of Lake of the Woods), Grassy Narrows is a semi-remote Anishinaabe community with an on-reserve population near 950. For generations, the people of Grassy Narrows have hunted, trapped, fished, and gathered throughout a vast 2,500-square-mile region drained by northwestern Ontario’s English-Wabigoon River system. Not only their livelihood, but their culture, language, and spirituality are closely connected to their boreal forest homeland.

In the 1990s, as industrial logging intensified across Canada, Anishinaabe subsistence harvesters watched clearcuts grow larger and draw closer to their 14-square-mile reserve with growing unease. They wrote letters to logging companies and government officials, but received no substantive response. They conducted peaceful protests in Kenora, Toronto, and Montreal, but the clearcutting continued. They requested environmental assessments and judicial reviews, but were only met with rejection and bureaucratic stalling. It was time to take a stand. One frigid early winter night, residents of Grassy Narrows decided enough was enough. Three young community members placed logs across a snow-covered logging road north of the reserve. They were soon joined by dozens of community leaders, teachers, and youth.

For most of us, ten years pass in the blink of an eye. In the whirlwind of family, friends, work, and life that fills each day (3,652 of them in this case) we rarely pause to take stock of what has or hasn’t changed. Anniversaries inspire this kind of reflection. In ten years, children become teenagers. Teenagers become adults and start families of their own. Beloved elders depart. And the rest of us continue traveling along the paths we choose—or the paths that choose us. The blockade has stood for ten years, but Grassy Narrows residents have fought for the right to make decisions concerning their traditional territory and to keep their land-based culture alive for much longer.

In 1873, the forefathers of Grassy Narrows (along with representatives of 26 other Anishinaabe groups) signed Treaty Three, the third of Canada’s numbered treaties. Although the agreement’s original intent (and therefore its contemporary interpretation) is debated, the official version of Treaty Three guaranteed that Aboriginal signatories would “have right to pursue their avocations of hunting and fishing throughout the tract surrendered.” The fact that industrial clearcutting—carried out under provincial licenses—infringes upon these federally guaranteed rights has figured prominently in blockaders’ position papers and press releases and was a central tenet of a legal challenge filed by three Grassy Narrows trappers in 1999.

The past 139 years have brought many changes to northwestern Ontario. Anishinaabe people throughout the region have been impacted by a series of culturally catastrophic impositions: year round settlement on small reserves, the 1876 Indian Act and associated assimilatory policies, and residential schooling top a long list. At Grassy Narrows, two additional events—relocation and mercury contamination—have compounded the damage with disastrous consequences. In the early 1960s, the Canadian government relocated and consolidated the First Nation’s population, promising on-reserve schooling for children, access to medical care, and modern infrastructure. The move dramatically disrupted traditional social organization patterns. Already struggling to cope with the effects of relocation, another blow was delivered in 1970. Mercury contamination—traced to the effluent of a pulp and paper mill located in far-upstream Dryden, Ontario—was discovered in the English-Wabigoon River system. As it flowed downstream, the mercury bioaccumulated in the tissues of small aquatic organisms, fish, and eventually Anishinaabe people. The effects on physical health, economic opportunities, and collective psychosocial security were severe.

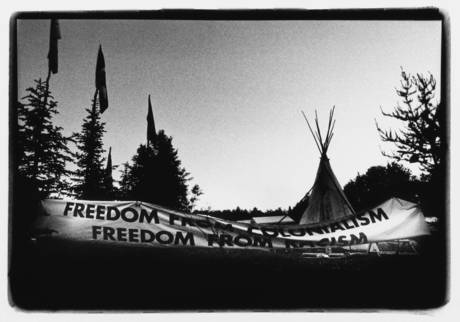

By 2002, stopping the clearcutting within Grassy Narrows’ traditional territory was the most immediate issue and most visible motive for direct action. Yet given that industrial logging is merely the latest in a long line of social and environmental injustices, protecting their boreal forest homeland is only part of the blockaders’ agenda: they are equally—and inseparably—concerned about asserting their inherent and treaty rights and renewing their land-based way of life. The cultural significance of Grassy Narrows’ direct action is apparent to anyone who has spent time at the blockade site. Shortly after the blockade began, the local school started holding on-site indigenous studies classes and community members started coming together at the blockade to share wild foods, participate in traditional spiritual ceremonies, and enjoy each other’s company.

As Canadian alternative media outlets spread word of the ongoing blockade, a network of supporters extended across Canada and beyond. Some individuals arrived at Grassy Narrows to lend a hand. Others sent words of encouragement or donated much-needed supplies and funds. Nonprofit groups also took up the cause: Rainforest Action Network, Christian Peacemaker Teams, and others worked to ensure that Grassy’s message was carried far and wide. The longest standing anti-logging blockade in Canadian history was reinforced by the countless environmentalists, human rights advocates, indigenous activists, and consumers of paper products who stood behind it and challenged corporations to yield to Grassy Narrows.

After five-and-a half years, the hard work of the blockaders and their allies began to pay off on the ground. In February of 2008 U.S. paper producer Boise-Cascade caved to an international solidarity campaign and declared that it would stop sourcing wood from Grassy Narrows territory unless Grassy Narrows consented to the logging. The company gave its supplier, AbitibiBowater (now Resolute Forest Products), a deadline of June 30. Facing an unyielding blockade, major contract cancellations, and appeals of their forest stewardship certification, on AbitibiBowater announced on June 5th that it was surrendering its license to log Grassy Narrows’ territory. Against all odds, Grassy Narrows succeeded in halting the flow of logs from the community’s customary landbase to the mills of multinational corporations and evicted the world’s largest newsprint company.

More recently, in August of 2011, the trappers’ lawsuit initiated in 1999 received a favorable decision in Ontario’s Superior Court (the ruling echoed blockaders’ argument that Ontario lacks legal authority to issue forestry licenses that interfere with treaty rights, which is an area of federal jurisdiction. The ruling has since been appealed and may ultimately be decided in Canada’s Supreme Court). Although logging companies remain eager to access the area’s valuable timber and recent provincial forest management plans leave the door open for this to occur, the hard-won hiatus from industrial logging remains in effect.

Putting an end (at least for the time being) to the clearcutting devastating Grassy Narrows’ traditional territory is a remarkable achievement and a tangible assertion of Grassy Narrows’ authority over its homeland. It will be celebrated once again by First Nation residents and hundreds of their supporters this December. But the story isn’t over. In addition to fears that industrial logging could return to the region, Grassy Narrows residents continue to seek justice for the long-term health effects of mercury contamination and the long-term sociocultural effects of relocation and residential schooling. Immured in a neocolonial system that places corporations’ bottom-lines above the wellbeing of indigenous citizens, the people of Grassy Narrow must now fight for what their ancestors once simply lived. They have no plans to back down. This too is something to celebrate. Their determined stance reminds us that corporate domination is neither complete nor inevitable, that alternative ways of life are worth fighting for.

Grassy Narrows First Nation is one of thousands of indigenous communities worldwide currently defending their lands and lifeways. For more information about Grassy Narrows First Nation, see http://freegrassy.org. To learn about other indigenous struggles see http://ienearth.org and http://www.culturalsurvival.org/.