Lest We Forget

Lest We Forget

Remembrance Day has become central to constructing dangerous myths about Canadian history. This is perhaps most worrying with regards to the claim that the two world wars forged a united Canada, as our soldiers defended freedom and democracy overseas.

Such a claim clashes with mountains of historical research demonstrating quite conclusively that the rights and democracy we have in Canada emerged from the struggles of workers, women, farmers, immigrants, and soldiers, fighting against war profiteering and widespread abuses of state power during the wars. The following is a brief survey of how the home front, not the beaches of Normandy or Vimy Ridge, was the crucible in which such freedoms were not simply defended but expanded through popular struggle.

The Class War

During both wars, rationing inflicted widespread hardship on the homefront. Real wages stagnated as living costs climbed rapidly. While full employment was assured through the war effort, the welfare state did not exist, making struggles over wages central to everybody’s concerns. All the while, civilians were encouraged through relentless state propaganda to police one another to prevent hoarding and black marketeering.

As millions lived through years of privation, scandals erupted repeatedly exposing government collusion with big business. This was epitomized in WWI by the infamous Ross Rifle debacle in which businessmen, politicians and top military officials colluded to profit off of arming soldiers with a rifle that jammed when wet or muddy. In this context, the Trades and Labour Congress launched a Conscription of Wealth campaign demanding business sacrifice their profits through high taxation.

Canada was caught up in a wave of anti-war and anti-government opposition sweeping most warring nations. Between 1916 and 1923, Europe was convulsed by mass mutinies, armed rebellions, general strikes, and revolutions.

Canada’s largest strike wave began in 1917 and lasted until 1921. With no mechanisms governing industrial relations, workers had to strike to achieve union recognition and collective bargaining rights from employers. Canada’s first general strike took place in August 1918 when anti-war labour activist Ginger Goodwin was murdered by police.

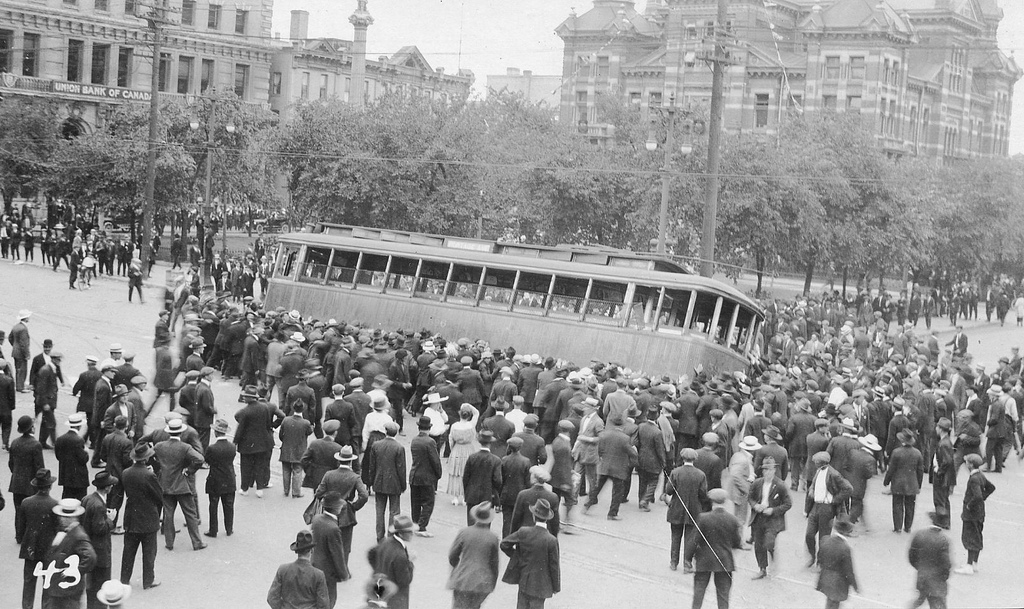

The strike wave escalated in 1919 with the Winnipeg General Strike. Few Canadians know that this was accompanied by general strikes in Vancouver, Edmonton, Calgary, Saskatoon, Regina, Toronto and the Nova Scotian manufacturing centre of Amherst. Repression was meted out against workers, with Winnipeg’s strike committee being arrested and its immigrant members being deported to war-torn Europe. Workers’ struggles persisted in Cape Breton until 1925 where communist-led coal miners and steelworkers took on greedy, government-backed employers. One quarter of the Canadian army was stationed in Cape Breton in the early 1920s to suppress the strikes.

A similar process unfolded in WWII when gold miners in Kirkland Lake struck for union recognition in 1941. The strike was defeated through brazen cooperation between government and employer. Galvanized by a pan-Canadian solidarity campaign for the gold miners, and building upon the lessons of the tumultuous 1930s, workers’ action escalated through the war. This compelled Mackenzie King to adopt Privy Council Order 1003 in 1944, which, for the first time, led the government to legally recognize unions and force employers to negotiate with unions. Shortly after the war, the stabilization of Canadian industrial relations known as the rand formula was achieved through the 99-day Ford strike in Windsor. The right to form a union and bargain collectively was secured on the home front by workers’ action.

The War for Democracy

In both wars, opposition to state power and austerity took on a political form as the first major wave of third-party breakthroughs happened across Canada. In 1919, Ontario elected a coalition government led by the United Farmers of Ontario and supported by the Independent Labor Party. The farmer-based Progressive Party became the official federal opposition in 1920 and the United Farmers of Alberta took power in 1921.

Meanwhile, women’s organizations successfully fought for the vote mainly at the provincial level while the federal government opportunistically introduced the vote to women serving overseas in order to win its pro-conscription election campaign of 1917. With women’s suffrage and the emergence of a multi-party system, it was popular pressure that expanded the meaning, understanding and practice of democracy in Canada.

During the 1940s, Canadians understood the necessity of combating fascism but still held deep reservations about the conduct of the war, war profiteering and conscription. Opposition to the ruling Liberals mounted quickly. In 1942, a federal Gallup poll showed the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation leading both the Liberals and Conservatives, even amongst Canadian soldiers overseas. The CCF became the BC opposition in 1942, narrowly lost the Ontario election in 1943 and took power in Saskatchewan in 1944. The war even saw Communists elected at the provincial level in Manitoba and Ontario and federally in 1945.

The demands placed on Prime Minister King by millions of Canadians was critical to secure the expansion of social, political and civil rights and the building blocks of the welfare state.

Challenging State Power

During both world wars, conscription was not enacted at the outset of war. Canadians remained loyal to the idea of an all-volunteer military and many viewed conscription with suspicion and a form of despotic power reserved for countries like Germany. This held up in 1914 as Canadians thought the war would be “over by Christmas.” Without even a vote in parliament, Canada entered the war alongside Britain –a war between contending European empires responsible for the brutal colonial conquests in Africa, unparalleled famines in the Indian subcontinent, the impoverishment of China and murderous adventures in the Middle East and Southeast Asia. The willingness to so quickly side with the British empire alienated Quebec’s francophone population.

Opposition to conscription led to protests through early 1918, culminating in the Easter riots in which English Canadian soldiers opened fire on an unarmed crowd in Quebec City, killing five, including a child, and wounding over a hundred. In December 1918, conscripts mutinied in Victoria and refused to serve in the fourteen nation effort to encircle and destroy the besieged revolution in Russia.

Conscription returned in 1944 despite Prime Minister King claiming otherwise during the 1940 election. A referendum was held in 1942, which again witnessed major opposition in Quebec.

In addition to the civil liberties repealed through the use of the War Measures Act in both wars, the Canadian government also targeted ethnic and racial groups labeled the enemy. Japanese-Canadians, the vast majority of whom were full Canadian citizens born in Canada, were taken from their homes mainly in British Columbia and sent to camps across Canada. Their homes, businesses, fishing fleets, and possessions were confiscated without compensation and never returned, even after the war. Fewer Canadians know that this also happened to immigrants from Germany, Italy, Hungary, Ukraine and other Eastern European nations during WWI.

The claim that Canada was united by the war does not hold up. Divisions between Quebec and Canada became increasingly prominent in both wars and class conflict escalated to record heights. Workers and farmers were central to the ushering in of a multi-party democracy and in WWI, for the first time, women secured the vote. The dramatic expansion of social and economic rights was also secured through workers struggles and the beginnings of the welfare state. Collusion between business and government in repealing fundamental freedoms, profiting from war production, and suppressing popular movements through force was the crucible in which Canadians further democratized the political system and dramatically expanded our rights and freedoms.

This article first appeared in the Leveller newspaper – Vol. 5, No. 3 (Nov/Dec 2012)