Where's the Party in Black History Month?

Where's the Party in Black History Month?

TORONTO–Of all the civil rights leaders and Black power groups to emerge during Black History Month discussions, events, festivities, and forums, the Black Panther Party remains one of the most misinterpreted, contentious, and underrepresented figures of the tumultuous 1960s Black Movement. Think “Black History Month,” and it is the figures of Nelson Mandela, Martin Luther King, Rosa Parks and Harriet Tubman who are celebrated across classrooms and campuses for their contributions to bettering the state of our Black communities. Rightfully so. But where is the Black Panther Party in our discussions? Who is the Black Panther Party?

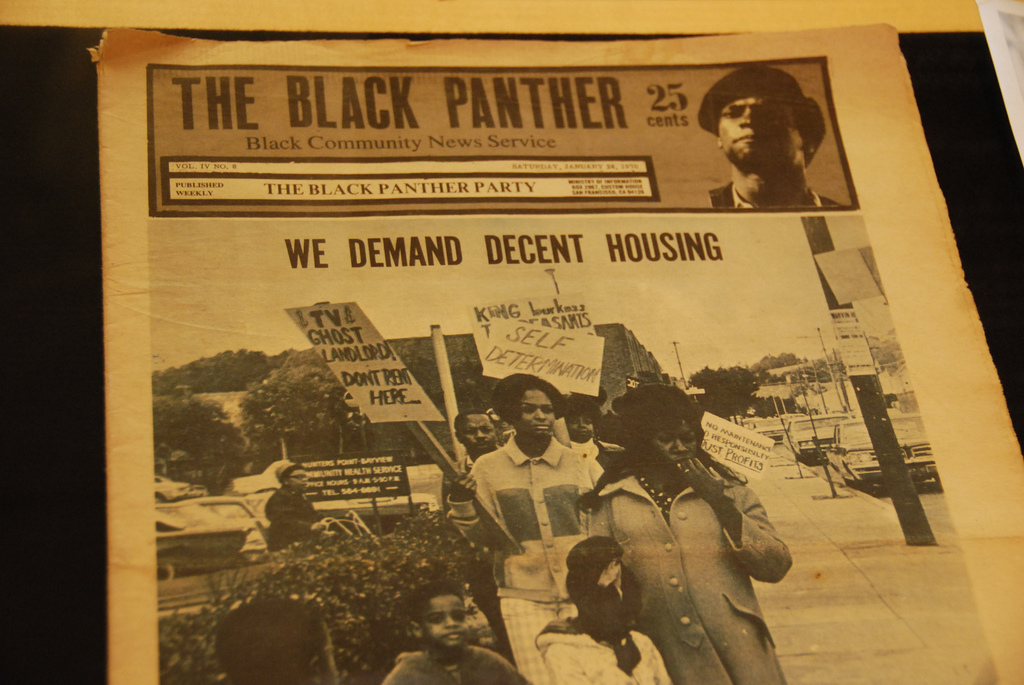

Provocative and militant in calling for Black self-determination, and later self-determination and political action for all oppressed people, the Black Panthers and their involvement in urban, Black communities is often overshadowed by their confrontational and sometimes violent tactics. Founded in 1966 in Oakland, California, by leaders Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, the Black Panther Party (originally titled the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense) was an African-American revolutionary leftist organization active across cities in the United States from 1966-1982. Seeking to empower poor, marginalized populations of the Black ghetto, the Black Panthers set forth a doctrine which, at first, called for the protection of African-American neighborhoods from police brutality but eventually turned into an organization devoted to Black liberation and revolutionary change. To further their socio-political goals, from 1966 until 1971 the Black Panther Party established a variety of community social programs focused on alleviating poverty, improving healthcare, education and understanding the criminal justice system: they formed Free Breakfast for Children programs, free health clinics, Liberation Schools, legal aid seminars, community alert patrols, and voting campaigns.

“I view the Panthers as the most significant Black Power political organization from the late 1960s and early 1970s, yet also one of the most misunderstood given America’s fascination with images and representations of political violence,” explains Ian Rocksborough, an academic who studies the history of the African American Left and cultural politics of New York and Chicago.

“Beyond their revolutionary élan, the Panthers more significant impact on the history of African American communities from that era was their support for local social reforms: leadership with the formation of much needed soup kitchens, anti-poverty campaigns, alternative neighborhood schools for inner-city children who attended under funded and neglected public schools, and much needed protection from predatory police violence,” Rocksborough details, adding that unfortunately much of what we know about the Black Panthers today gets tied up with the tragic life stories of the group’s prolific leaders, most of whom were either assassinated or incarcerated.

Perhaps therein lays the main reason the Black Panther Party is only hesitantly celebrated, let alone acknowledged during Black History Month. While the Black Panthers, among other principles, called for freedom, full employment, decent housing, education, an end to police brutality and murder, and access to land, bread, clothing, justice, and peace for all Blacks living in America, the group was regularly embroiled in violent public confrontations and employed, what some would call, a violent aesthetic. Panthers chanted slogans like “Off the pigs”; Black Panther Party Chief of Staff David Hillard threatened to a packed crowd in San Fransisco that “We will kill Richard Nixon”; the group acquired guns and ammunition, and recruited hundreds of estranged Vietnam veterans to train in underground cells in the art of guerilla combat. These all are good reasons why the line between rhetoric and reality is easily confused with the Black Panther Party, argues scholar Ryan J. Kirkby in an essay titled The Revolution Will Not Be Televised: Community Activism and the Black Panther Party.

The group’s controversial Community Alert Patrol which saw Panthers take their guns to the streets to defend community members being harassed by police became their most controversial and highly publicized program. Panther members witnessing young black “brothers or sisters” in a compromising situation with officers, would approach the scene and, if deemed reasonable, attend the scene of the dispute and inform the arrestee of their constitutional rights.

“It is easier to embrace peace and love rather than violence and hate,” explains Dr. Paul Lawrie, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Toronto studying modern African American labor and history, on why North American society is reluctant to celebrate the Black Panther Party during Black History Month.

“Across the political spectrum – whether liberal or conservative – Black people acting in self-interest in a violent way is not something we’re cool with. The Black Panthers’ rhetoric and aesthetic of violence, their right to carry weapons, the black jackets, Newton’s knowledge of the law…there is a real unease with societal liberation especially when coming from Black people.”

It is hard to understand society’s demonization of the Black Panthers and our reluctance to acknowledge the group’s contributions to Black communities across North America when we consider that, at least in the U.S., “violence as part of American culture, is as American as apple pie.” While violence may not be a part of what some call our “Canadian mosaic,” we still need to critically think why it is that powerful, white leaders embracing violence are fine to acknowledge, admire, academically discuss and celebrate in this country, yet a powerful Black group attempting to get their pressing political goals across in the same way is not.

“That’s been the one taboo…that black people and other oppressed people in this country are never to use violence to achieve what it is they want. But [America] uses violence whenever it chooses, and then it legitimizes the violence,” says Bird, a character in Made In America: Crips and Bloods, a film which discusses the Civil Rights Movement and Black Panther involvement.

Whether one agrees or disagrees with the Black Panthers stance on revolutionary violence, the media’s dominant narrative depicting the group as violent terrorists, alongside the FBI saying, at the time, that the party is “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country,” has contributed to our unwillingness to celebrate the Black Panther Party today. These reasons also led to the end of the Black Panthers: in 1982 the Black Panther Party dissolved and while the FBI’s extensive program (COINTELPRO) of surveillance, infiltration, perjury, police harassment, assassination and other tactics designed to undermine Panther leadership played a key role, so too did other factors. Power struggles within the group, divisions between Panther members and the Black community about the place for violence in revolution, alongside drug infiltration of the Party resulted in the disintegration of the Black Panther Party. Has all this drama left a bad taste in our mouths?

In Canada that answer may very well be yes. As a nation which says to pride itself on peaceful and non-violent intervention to social, economic, and political struggles, it may very well be that, for many, the Black Panther Party is simply not a culturally appropriate group to celebrate during Black History Month.

We saw that across Black History Month celebrations in Toronto in February 2012, where empowerment through non-violence was a constant theme. Last year’s Decolonizing Our Minds, an annual event put on by the Equity Studies student body at the University of Toronto featured a panel discussion on the topic of Resistance through Non-Violence; the Global Afrikan Congress hosted a panel discussion on the topic of Black racism in the Canadian criminal system with several speakers arguing that in order to address systemic racism and racial discrimination “we need to fight [but] the masters tools cannot be used to dismantle the masters house. We [Blacks] need to operate outside the box.”

To think that by celebrating the Black Panther Party during Black History Month we legitimize violence is not only false but also depreciates the meaning of Black History Month and the historic struggles Blacks in North America have had to face. We have to understand that Panther violence was not unprovoked. And herein lays the key message: we don’t necessarily have to agree with Black Panther tactics. What we do have to do is understand from what kind of place the anger and aggression came from and celebrate the courage of the Party to rise above systemic racism and political oppression, stand up to the White man, and demand equality.

“History is about the totality of our lived experiences. A complex reading of the Black Panther Party and their ideas about decolonization, emancipation is key. We cannot gloss over [the] violence of [our] history, we owe it to our own people,” argues George Dei, Professor of Sociology and Equity Studies at the University of Toronto.

Dei explains that we need to think critically about the dominant narrative that is told of the Black Panther Party and in a broader sense, understand what the movement was about.

“Black History Month has become commoditized and a sincerity needs to be brought back to it. Struggle, resistance, liberation – learning about [Black] contributions to the world should make us proud, should take us to another level and improve our conditions,” Dei enlightens about the role Black History Month should play.

“How do we [Blacks] improve the present situation? What does this history mean? Learning this history how do we come together to create healthy, sustainable communities?” This is what Black History Month should be about, insists Dei.

The Black Panther Party not only challenges us to ask ourselves these difficult questions but also dares us to fight and intervene, by all means necessary, any forms of oppression. And if anything, that is certainly something worth celebrating.