Family's Stayed Deportation Highlights Systemic Deficiencies of 'Sanctuary Cities'

Apr 12, 2019

Family's Stayed Deportation Highlights Systemic Deficiencies of 'Sanctuary Cities'

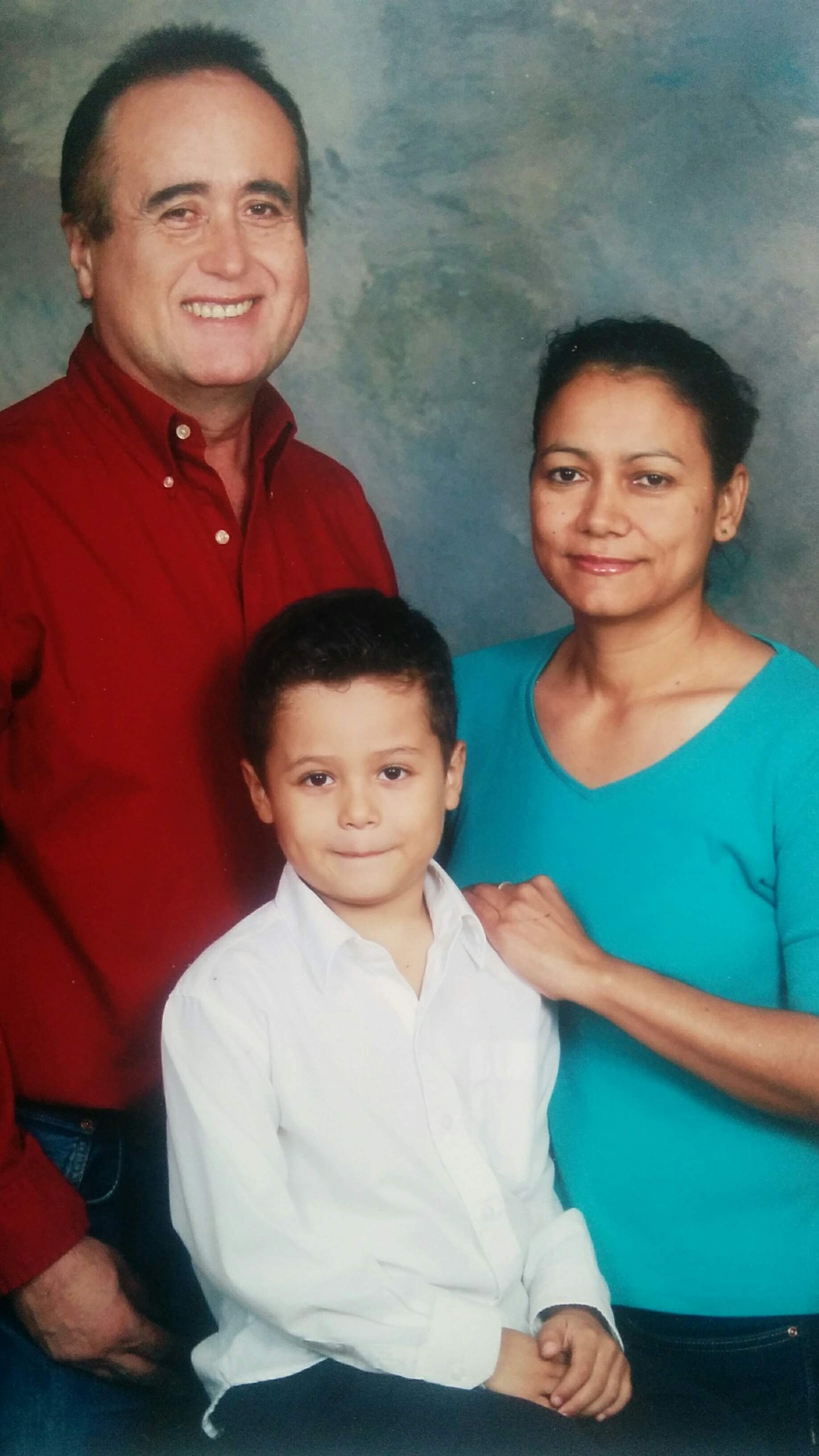

At about 11:30 a.m. on Wednesday, April 3, Jorge Orozco and his wife Rosalba Solares began to reluctantly pack their bags inside their Toronto apartment. Their seven-year-old son, Julian, stood quietly in the room, watching “in shock” as his parents, who faced deportation, tried to stuff their entire lives into two suitcases.

“Twelve years of being here (in Canada),” Jorge says in Spanish, “and all we could pack was 50 lbs. each. It doesn’t make sense.”

If the order had gone through, Jorge would have been deported to Colombia, where the conflict between guerilla fighters and government forces have displaced millions like himself for decades. Rosalba would have been sent back to Guatemala, where a violent ex-boyfriend who she says belonged to a gang was waiting to kill her. With no family in Canada, Julian was set to go with her.

Then, around 11:40, their lawyer called. The order had been stayed.

“It was like we were born again,” says Jorge. “It was very emotional for us.”

The stay means they now will be able to remain in Canada until a decision is made on their application for permanent residence based on humanitarian and compassionate grounds.

But their case highlights the systemic deficiencies that allow refugee and asylum seekers to be routinely intimidated and mistreated at the hands of the Canada Border Services Agency and the impacts this has on their physical and mental health, even in so-called sanctuary cities such as Toronto.

Irreparable Harm

In granting the stay, Justice James W. O'Reilly wrote in his ruling that despite the fact his parents had broken immigration laws, “Julian would suffer irreparable harm if he and his parents were removed from Canada.”

"That harm flows from family separation, interruption of his school year, severing social ties to Canada, risk of serious health consequences, and risk of harm in Guatemala,” he wrote.

But according to Dr. Paul Caulford, a family physician at the Canadian Centre for Refugee & Immigrant HealthCare who's been treating the Orozcos since 2013, a lot of that damage has already been caused by years of mistreatment by the CBSA.

Describing them as “very humble, dignified people,” Caulford says the Orozcos were at first a happy family “building a new life with hope” when they arrived in 2007. That same year they had also applied for asylum, but it would take four years until 2011 for that to be officially denied. Still, says Caulford, there was a “different psychological dynamic” then. “They were still fighting.”

But since July of last year, after Jorge got into a car accident, things went from bad to worse when the police alerted the CBSA of their immigration status. By March, they found out they would be deported separately.

Since then, the family has gone into a “downward spiral,” says Caulford, though they put on a “brave front.” Julian has even begun showing signs of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. His sleep patterns have also been disrupted, he’s lost weight and has become quiet.

“His smiles were forced,” says Caulford referring to some their latest visits. “I’ve never seen him so quiet. He was always so jovial.”

Jorge also noted how distanced Julian had become and the “trauma” he had undergone. Even his first-grade teacher had noticed a dramatic change in him over the last year, he said.

“When his teacher saw him she was surprised and asked where his smile had gone and why he seemed so sad,” says Jorge. “When (Julian) told her, she broke down in tears.”

In an email response, CBSA spokesperson Nicholas Dorion told the Media Co-op that while “(h)aving a Canadian born child is not an impediment to removal...the CBSA always considers the best interest of the child before removing someone.”

Caulford sees it differently.

According to him, in a recent court hearing, a CBSA agent even “lied” on record when he claimed the doctor was a friend of the family “in order to harm the objectivity of Julian’s case.” The point, he said, was to set a precedent that would deter physicians like himself from advocating for their patients in the future.

“This was reprehensible behaviour (and) a clear abuse of the justice system,” he said, adding that their actions had bordered on “child abuse.”

Dorion did not provide answers to a direct question about these allegations.

Advocacy essential for human rights

Stacey Gomez, a coordinator with the Maritimes-Guatemala Breaking the Silence Network- BTS says the problem is system-wide, because national immigration policies give the CBSA too much power and room to abuse it. Even in places like Toronto, for instance, police routinely contribute information to the CBSA, violating the very spirit of the so-called sanctuary city.

Last year, No One Is Illegal - Toronto pushed police to implement a don’t-ask, don’t tell policy after the advocacy group compiled a list of more than 3,200 times cops had called the CBSA from November 2014 to June 2015, the CBC reported.

“So it’s clear the policies of sanctuary cities are not working,” Gomez said. “It doesn’t mean broad protection for migrants.”

In the Orozco’s case, it was after Jorge’s 2018 car accident that the police alerted the CBSA of their status.

This type of inter-agency collaboration can only increase, as the CBSA announced last year that they intend to ramp up deportations by 25 - 35 percent, or 10,000 people, annually.

According to the CBC, which first revealed the CBSA’s new targets last October, over 18,000 cases are currently in the deportation queue, most of them failed refugee claimants like the Orozcos.

But immigrant advocates such as Gomez say the issue is not that there’s a backlog of deportations waiting to happen, but that too many obstacles are put in place for people seeking asylum for “legitimate reasons” in the first place.

This is because “Canada is not doing sufficient work to meet its international obligations to accept refugees,” she said. “The system is too stringent, which means many people can’t qualify."

Even when people like the Orozcos try to abide by the process to obtain their documents, they come up against a system inherently designed to block them.

On Monday, April 8, for instance, the Federal Liberals quietly introduced Bill C-97 inside a 392-page omnibus budget bill. If passed, the law would prevent asylum seekers whose applications have been denied elsewhere from applying for refuge here.

“It’s very uncomfortable for us to think we are here illegally,” says Jorge, conceding there’s a process they must go through.

“But it gets even more complicated...with a deportation order, because you have to always hide.”

As a physician, Caulford therefore sees advocacy from civil society, including from the healthcare community, as “absolutely essential for the human rights” of migrants.

“Advocacy is critical for failed refugee claimants,” he said, because “they are immediately turned into undocumented migrants...and their rights go down the tube.”

That is why he insists that immigration history must be shared among healthcare physicians, particularly those who deal with new Canadians as they may limit what they disclose out of fear of deportation. But if their medical history were better known, it may help their cases.

What has legality to do with it?

Jorge has a brain condition that will likely worsen if he is forced to go to Colombia, which would limit his access to the medication and treatment he needs, explained Caulford. As an undocumented immigrant appealing his case, this is yet another looming threat hanging over his head.

But “what has legality to do...with (access to) healthcare? And who among us is perfectly legal anyway,” Caulford said, referring as an example to the many tax-evaders whose white-collar crimes don’t disqualify them from accessing medical services.

And yet, despite all the hardships the system has put them through, the Orozco family remains grateful for the opportunity at peace they have found in Canada, and for the communities and advocates that have rallied and supported them.

In the end, their message is a simple, but powerful one.

“We ask (the Canadian government) to please not separate our family,” says Jorge. “We are honest people, we are hard-working, and we have much to offer Canada.”