Medical Errors

Medical Errors

MONTREAL—Resident doctor Alexander Nataros had just begun his evening rounds of the emergency department at St. Mary’s Hospital last November when he came upon a man in near- critical condition. The man, who was lying in one of the beds that line the hallways of the McGill University affiliated hospital, had a severe facial droop and a chronic case of hiccups, which suggested increased intra-cranial pressure.

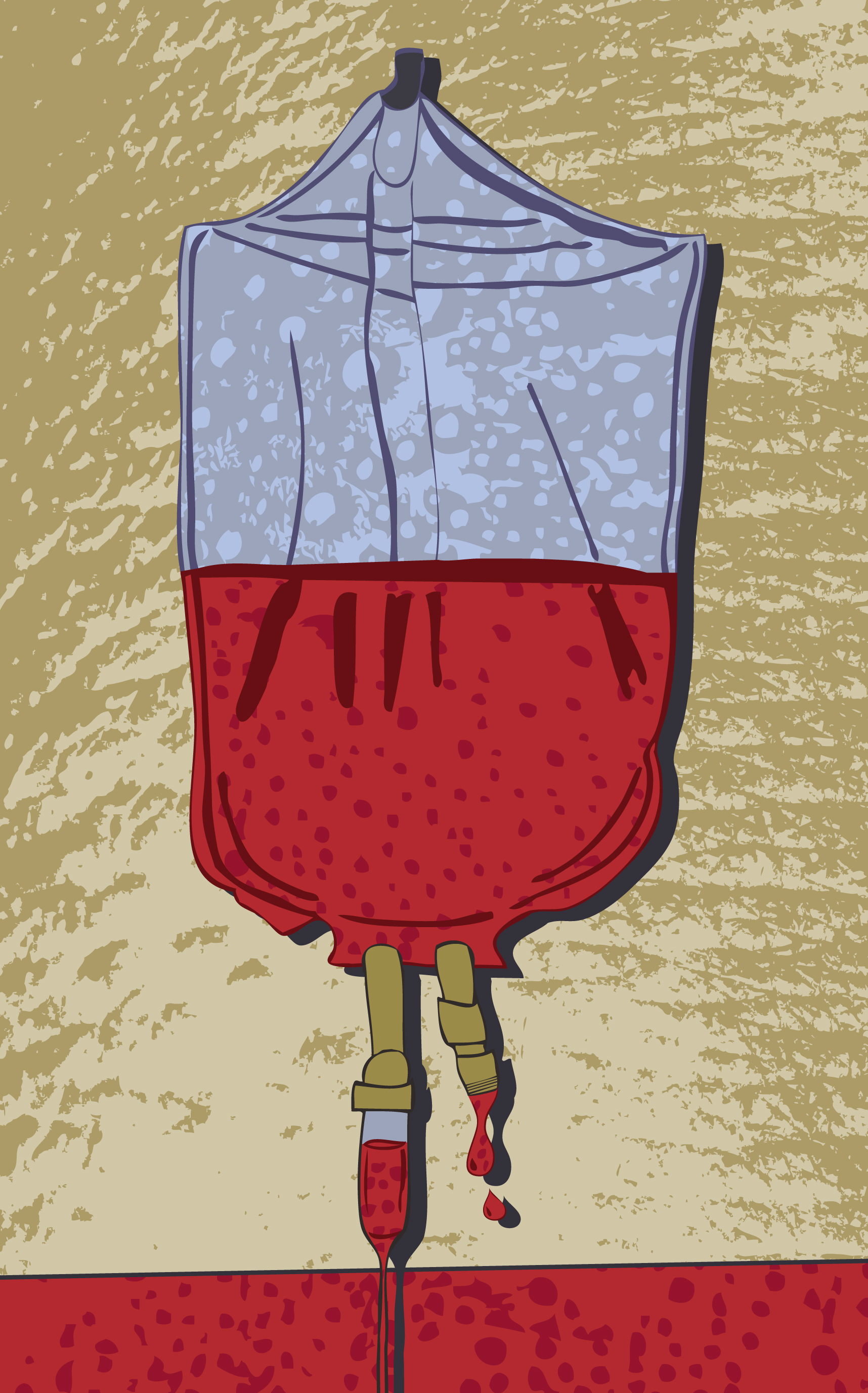

Drawing on the limited neurological training he had received in his fourth year at the McGill Faculty of Medicine, Dr. Nataros swung into action, inspecting a CT scan that had been ordered by the previous resident. The test confirmed what Dr. Nataros already suspected: there was blood in the man’s brain, likely the result of a hemorrhagic stroke. The patient also had a blocked airway and was on the verge of asphyxiation. Dr. Nataros gave the man an infusion and wheeled him into the “crash” room, where a second-year medical student intubated the patient. Together, they succeeded in stabilizing the man, who was then whisked off in an ambulance to a nearby tertiary care centre. While relieved that the fatality had been averted, as he resumed his rounds, Dr. Nataros was bothered by the nagging thought that the crisis should have never happened in the first place.

In a telephone interview in March, Dr. Nataros told The Dominion that the stroke victim, whose life he had saved, was given the wrong treatment over the course of two days by two senior physicians. According to Dr. Nataros, the doctors had misdiagnosed the patient with a mild heart attack, and given him medication that caused his blood to thin. “It was more than just the wrong treatment,” said the junior doctor, who has youthful features and brown hair. “There was a missed diagnosis that made it infinitely worse, and the patient almost died.”

Dr. Nataros said that when he decided to report the medical errors, the doctors involved in the incident responded by getting a number of their colleagues to write letters accusing him of being argumentative and disrespecting authority. He also said that Dr. Sarkis Meterissian, the Postgraduate Director of Family Medicine at McGill University, attempted to defame his name. In a letter, which Dr. Nataros provided to The Dominion, Dr. Meterissian suggested that Dr. Nataros may suffer from a mental illness and requested that he undergo a medical evaluation.

Dr. Meterissian told The Dominion he could not comment on the specifics of Dr. Nataros’ case because the matter was currently in front of the Collège des médecins du Québec (the province’s professional order of physicians). Dr. Nataros claimed that the treatment he has received is an example of the intimidation that many med students and young doctors face at the McGill University Health Centre’s (MUHC) teaching hospitals, and that he has witnessed many instances of verbal abuse and taunting. “These things go unchallenged because they are accepted in the culture.” He also said that he is worried that the overly hierarchical relationship between senior doctors and their students at these institutions can often dissuade med students and young doctors from reporting medical errors.

In January, Dr. Nataros was placed on academic probation and forced to take a paid leave of absence from his family medicine practice at St. Mary’s. An independent ombudsperson is investigating the incident he reported. He went public with his story after exhausting all formal avenues of complaint, including two review panels, despite favourable testimonials from more than a dozen senior doctors who had worked with him and were willing to vouch for Dr. Nataros’ professional competence.

Dr. Nataros stressed that he did not report the errors because he wants the doctors involved to be punished, but because he believes there is much to learn from the experience. “I don’t want to blame anyone,” said the doctor, who grew up in BC in a family that included six doctors (two of his grandparents graduated from McGill). “I want this to be a learning experience and I want us to be able to have a safe space where we can point out such things so that future mistakes are corrected, and so people don’t suffer and die.”

Beyond a few unsigned letters of support addressed to the administration, none of Dr. Nataros’ peers have officially come forward in his defense. However, a number of graduates of the McGill Faculty of Medicine, as well as of the nursing program, agreed to speak to The Dominion if they were quoted anonymously. They reaffirmed that Dr. Nataros’ case is emblematic of a deeply entrenched culture of abuse and intimidation at McGill affiliated hospitals.

One doctor, who graduated from the McGill medical program in 2008 and is currently stationed at the Ottawa General Hospital, said when she was on call at St. Mary’s she frequently saw patients mistreated but was afraid to report the incidents because she feared how her professors would respond. “I’m still trying to figure out why I had such a hard time speaking up,” said the doctor. “I think it was because I was scared of them. I was scared that I was going to be failed. It was an unsaid thing.” The intimidating atmosphere and late-night shifts with an understaffed workforce would eventually prompt her to take sick leave twice for clinical depression. “I think it was the combination of being scared that I would kill [one of the patients] and the constant intimidation during the day, I just couldn’t take it anymore,” she said.

Another recent McGill graduate told The Dominion that her fellow medical students were mistreated by senior doctors. “I have many colleagues who had negative experiences at McGill, much like Alex [Nataros], and it doesn't surprise me that this negative environment led to medical errors,” she said. A recent graduate of the McGill nursing program said verbal abuse from supervisors prompted a number of nurses to switch career paths. “Many ended up doing research or other things like administration because they felt the hospital wasn’t a healthy environment,” he said.

Dr. Thomas Perry, a Clinical Assistant Professor at UBC and a McGill alumnus, said that he was disturbed that the McGill Faculty of Medicine had been accused of trying to muzzle a whistleblower. He was also surprised that the department had not figured out a way to resolve the conflict early on. “I find it baffling. I mean why not just put this to bed?” mused Dr. Perry.

Dr. Perry has seen firsthand how an overly hierarchical system can lead to medical errors. As a third-year medical student working a late night at the Montreal General Hospital in 1977, he watched—too afraid to say a word—as a surgeon performed what Dr. Perry knew was the wrong operation on a man with diabetes who had to have his parotid gland removed. Dr. Perry vividly remembers the incident. “The drapes were spread all over the man’s face. It looked to me like the doctor was operating on the wrong part…the gland is under the ear and they were going closer to the jaw, but, I figured I must be mixed up, the drapes must have disoriented me. I thought, little old me, third-year medical student, there’s no possibility I’m right. I did consider saying something about it before they cut but I suppressed myself, thinking I couldn’t possibly be right. And then when the drapes came off, I realized the wrong operation had been done.”

Although Dr. Perry reported the error immediately to the associate dean of medicine, it was initially covered up by the doctors involved in the incident and it took four months before the truth was finally revealed. Fortunately, the patient survived and eventually received the correct operation.

In their recently published book, After the Error, Susan McIver and Robin Wyndham note that roughly 38,000 to 43,000 deaths are attributed to healthcare delivery every year in Canada. According to McIver and Wyndham, the total number of deaths is significantly greater due to the high rates of non-reporting. Sholom Glouberman, the president of the Patients’ Association of Canada, cautions that it is difficult to get an accurate picture from the data because the baseline for what these systems will generate in terms of an “acceptable” amount of human error has yet to be determined. “Some people say, ‘Oh, well there should be no medical errors.’ Well that’s ridiculous,” he said. “There are always going to be errors in any system and you have to talk about what the baseline is in a complex system like healthcare.”

There is no doubt that medical errors can have devastating repercussions for patients and their families. In May, the Collège des médecins du Québec called on the well-known surgeon Peter Metrakos to explain before its disciplinary council events that led to the death of a patient named Ivan Todorov on February 1, 2010, less than three months after his surgery at the MUHC’s Royal Victoria Hospital.

A week before Todorov died, his daughter Dolia asked a pathologist for an independent investigation of a list of medical errors that included mixed-up files, a chemotherapy overdose, a major vein cut during surgery, no food for weeks, and an untreated E. coli infection. The pathologist referred the case to coroner Claude Brochu when the patient was on the verge of death.

When Brochu issued his report on October 19, 2010, he raised serious questions about the care Todorov received at the MUHC’s Royal Victoria Hospital and the Lakeshore Hospital. Now, the Collège is accusing Metrakos of failing to properly assess Todorov’s medical condition before the operation and conducting an operation that was not medically necessary.

According to the provincial registry’s latest data, there were 219,234 errors and accidents between April and September 2012 in Quebec hospitals. Patricia Lefebvre, coordinator of the MUHC Quality, Patient Safety and Performance Department, recently told the Montreal Gazette that although progress had been made through increased transparency, under-reporting remained an issue at the McGill affiliated hospitals. With little access granted to the press and the general public, the MUHC hospitals, like most Canadian hospitals, have a tradition of being nearly impenetrable when it comes to obtaining realistic estimates of medical errors.

Scoring a short break from work to speak to The Dominion last April, Dr. Ken Flegel walked through a maze of hallways to a small break room around the corner from his office on the fourth floor of the Royal Victoria Hospital. Dr. Flegel, who is a Professor and Consultant Internist at the MUHC and McGill University, is a slight man with dirty blond hair parted to the side, thin-rimmed glasses and a soft and deliberate way of speaking. He acknowledged that there is likely a link between under-reporting, irresponsible conduct and medical errors. “If you’re not having people reporting in a transparent way and giving clear and considerate advice, that’s a recipe for bad things to happen which probably could include patient errors,” he said.

He also said that the hierarchical culture, which he acknowledged borders on medieval, is gradually softening vis-Ã -vis professor-student power relations. “I think that the faculty is trying hard to engender that atmosphere,” said Flegel who is also the Senior Associate Editor of the Canadian Medical Association Journal. “The clinical world graduated a lot of them [senior doctors] a long time ago, so it sometimes takes a while for new attitudes and policies to penetrate.”

In 2010, the McGill Faculty of Medicine was threatened with probation by some of the medical school accrediting bodies due to a failure to meet 13 of 132 national standards. One of the charges against the university was the insufficient promotion of independent learning. Approximately two years ago, the McGill Faculty of Medicine recognized that verbal abuse and intimidation had become serious issues and launched an in-depth study of the mistreatment of med students and residents, resulting in the development of a new code of conduct. In an email to The Dominion, Dr. David Eidelman, Dean of the Faculty of Medicine, pointed out that the code is widely promoted among faculty, students and residents.

The McGill Faculty of Medicine allowed Dr. Nataros to return to work at St. Mary’s Hospital in late July. The independent ombudsperson has yet to make a decision about the report that he filed in November 2012. In March, Dr. Nataros told The Dominion that certain errors will never be documented unless doctors feel that it is safe to speak up without jeopardizing their careers. “We need to provide protection for whistleblowers because they will identify the errors,” he said. “And as long as they are not severely penalized, you will protect and save patients’ lives.”

Brendan K. Edwards is a Montreal-based freelance journalist who has written for Art Threat and the Montreal Media Co-op.